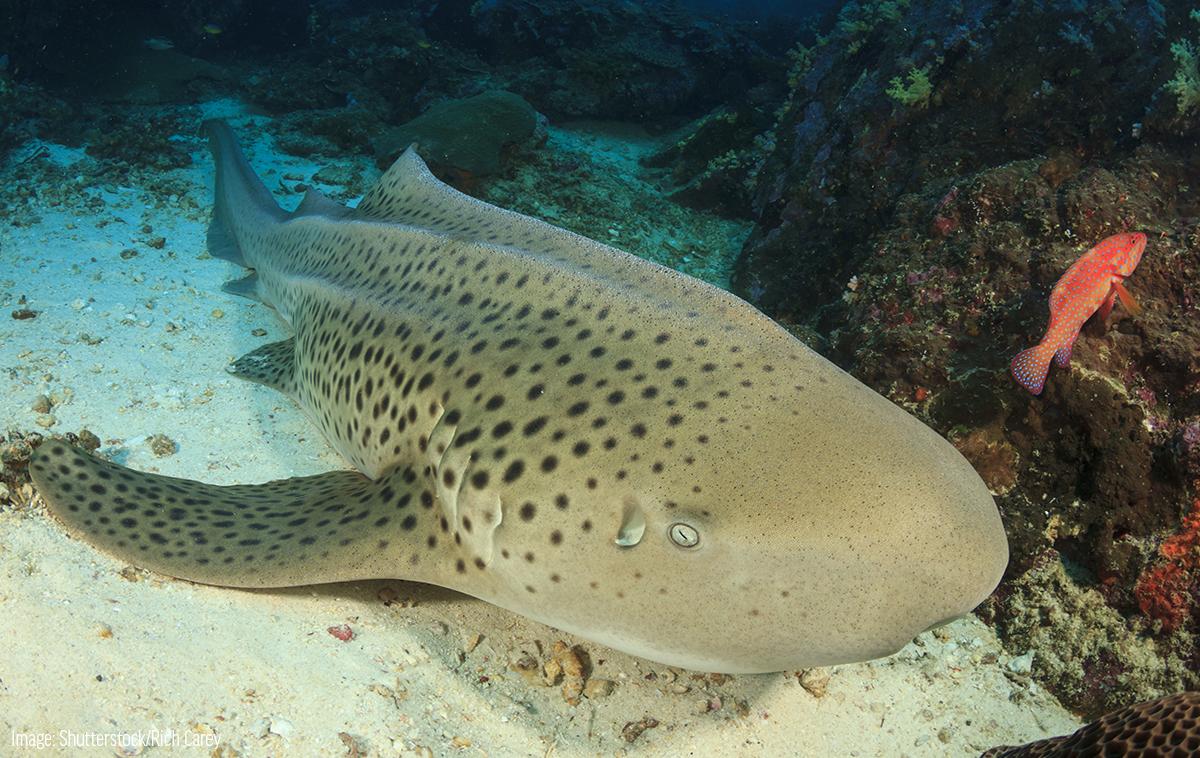

But there are some cases where particular species may benefit from extra help. Leave alone areas of the ocean where fishing and other threats are curtailed and marine populations should bounce back. In plenty of cases, ocean reintroductions shouldn’t be necessary because the seas have a tremendous capacity to rewild themselves, given a chance. Attempts to bring the last few vaquita porpoises into captivity from the Gulf of California went horribly wrong in 2017, when one panicked and had to be immediately set free, and a second swiftly died of a stress-induced heart attack. We’ll probably never see animals such as great white sharks or hammerheads or narwhals living and breeding in aquariums, then being released to the wild. “Unless you’re taking animals from one place and putting them in the other place in the ocean, you don’t really have that many options.”įor many aquatic animals, captive breeding and rewilding are just not going to happen. “There’s not a lot of them that are propagated or bred and successfully reared in human care,” says Julie Levans from Virginia Aquarium, about 150 miles south of Washington DC. Guarding a giant clam that stays put is difficult enough preventing other species from swimming straight into a fishing net is another matter This reluctance comes down, in part, to a lack of captive-bred marine animals to release into the wild. There are lots of ideas, such as bringing back grey whales to the Atlantic, or Dalmatian pelicans to the UK, but so far only a few have actually been tried out. But the notion of returning large, charismatic animals to the ocean is only just beginning to catch on.

With no firm definition, initiatives to replant seagrass meadows and re-establish extinct oyster reefs arguably come under the rewilding umbrella.

When it comes to putting back lost and vanishing species, be it Yellowstone wolves or British beavers, the underwater realm has been trailing behind its terrestrial counterparts. Giant clam reintroduction is a relatively rare case of what on landmight be called rewilding. However, the cages also exclude herbivorous fish, so the clams can easily get overgrown by seaweed, which is where the regular toothbrushing comes in. They’re still vulnerable to fishing and poaching, but if carefully guarded the giant clams do well and have become symbols of healthy corals reefs inside well-managed marine protected areas.Ī key to their early survival is rearing them in cages to keep them safe from predators until they’re large enough to survive by themselves. Australian clams were imported to start a captive breeding programme, and subsequent generations of their offspring have been released on coral reefs across Fiji. Here in Fiji, giant clams or vasua as they are known, were so heavily overfished for their meat and shells that by the 1980s they were thought to be extinct locally. It’s a giant clam but a young one and still just a handful. K neeling on the seabed a few metres underwater, I pick up a clam and begin gently cleaning its furrowed, porcelain smile with a toothbrush.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)